Financial services and criminal proceedings – ECJ clarifies approach

(Last updated: )

On 20 March 2018, the European Court of Justice (the “ECJ”) handed down four judgments in response to requests for preliminary rulings[1] on the interpretation under European law of the so-called ne bis in idem principle, i.e. the right not to be tried or punished twice for the same offence, also known as double jeopardy.

The cases at issue concerned the imposition of administrative sanctions (i.e. fines and bans on holding office) and criminal sanctions (i.e. fines and imprisonment) on the same individuals in the context of securities market manipulation, insider dealing and non-payment of VAT, and may consequently be of interest to anyone working in the financial services industry. The ECJ’s approach provides helpful clarification on the scope of recent case law from the European Court of Human Rights (the “ECtHR”). A more detailed overview of the legal background, the disputes in question, the analysis of the court and why it matters is provided below, however, those with a more limited interest in the subject matter are invited to jump directly to the key takeaways below, which also cover impending Brexit considerations.

Background to the jurisprudential developments

The legal doctrine of ne bis in idem is enshrined in European law in nearly identical form in Article 4 of Protocol 7 of the European Convention on Human Rights (the “ECHR”)[2] and Article 50[3] of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (the “Charter”). By way of elaboration, dating from 1953, the ECHR is an international treaty for the protection of human rights now entered into by the 47 countries comprising the Council of Europe (currently including all EU Member States and various non-EU countries). The ECHR applies to all national legislation. The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg has jurisdiction to hear applications on and enforce the provisions of the ECHR.

By contrast, the Charter is an instrument of EU law incorporating many of the protections afforded by the ECHR into EU law. The Charter was drafted in 2000 and incorporated into EU law under the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 as Article 6 of the amended Treaty on European Union. The Charter only applies in the context of interpretation of EU law. The interpretation of the provisions of the Charter are under the jurisdiction of the ECJ in Luxembourg. However, given the near-identical nature of many of the provisions in the Charter and in the ECHR and, for the sake of avoiding unnecessary divergences in their interpretation by the two courts, Article 52(3) of the Charter[4] requires that the rights contained in the Charter that correspond to the rights contained in the ECHR are to be interpreted to be the same in meaning and scope – but that this does not prevent the EU from providing more extensive protection. In practice, judicial comity has meant that, subject to certain nuances, both courts pay broadly equal respect to each other’s case law for the sake of a consistent application of human rights principles.

Broadly speaking, both courts have regard to the following criteria in the interpretation of the ne bis in idem principle:

- The person prosecuted or on whom the penalty is imposed is the same;

- The acts being judged are the same (idem);

- There are two sets of proceedings in which a penalty is imposed (bis); and

- One of the two decisions is final.

The interpretation of these criteria by the courts has over the past decade resulted in increasingly applicant-friendly case law. For example, in a seminal judgment in the case of Zolotukhin v Russia[5] in 2009, the ECtHR held that ne bis in idem prohibits the punishment of a second offence on the basis of acts which are identical to or substantially the same as those which were the basis for the first offence, whatever its legal classification. Similarly, in another significant judgment, in the context of a reference for a preliminary ruling from Sweden in the case of Åkerberg Fransson[6] in 2013, the ECJ clarified, broadly speaking, that a Member State could not impose successive penalties on the same individual for the same acts in so far as these penalties were criminal in their nature.[7] It is not necessary to address the details of these judgments for the purposes of this article, however, it suffices to say that their combined significance was such that, after Åkerberg Fransson, the Swedish Supreme Court ordered that restitution had to be given to everyone in Sweden who had been sentenced for tax fraud since the date of the Zolotukhin judgment.

This trend towards increased protection for individuals was disrupted in 2016 in the case of A and B v Norway.[8] In a somewhat controversial judgment, the ECtHR concluded that “for the Court to be satisfied that there is no duplication of trial or punishment (bis) as proscribed by Article 4 of Protocol No.7, the respondent State must demonstrate convincingly that the dual proceedings in question have been “sufficiently closely connected in substance and time”.” The “sufficiently closely connected in substance and time” test became the subject of considerable criticism, not least from the dissenting judge in the case. For these purposes,[9] it suffices to state that the court’s approach arguably constituted a significant step backwards in the protection afforded to individuals under the ne bis in idem principle. Furthermore, the ECtHR did not provide specific criteria for the application of the test of being “sufficiently closely connected in substance and time”, only stating that it was not necessary for the criminal and administrative proceedings to be conducted simultaneously from beginning to end but that, the greater the time difference between the two sets of proceedings, the more difficult it would be for the state to justify that difference. In combination with successive ECtHR case law,[10] the application of this test in the words of the Advocate-General[11] (“AG”) Campos Sánchez-Bordona “emphasises the almost insurmountable obstacles which national courts must address in order to ascertain a priori, with a minimum degree of certainty and foreseeability, when that temporal connection exists.”[12] For what it’s worth, it is the view of many observers that, in reaching this outcome, the ECtHR may at least to some degree have been influenced by arguably political considerations, principally in response to criticism from state governments regarding the broad interpretation of Åkerberg Fransson.[13]

It is against this backdrop that the ECJ came to address four requests for a reference for a preliminary ruling from Italy in the cases of Menci,[14] Garlsson Real Estate[15] and the joined cases of Enzo Di Puma and Zecca.[16] These four cases concerned the imposition of administrative penalties and criminal penalties on various individuals in alleged violation of the ne bis in idem principle in the context of VAT evasion (Menci), market manipulation (Garlsson) and insider trading (Enzo Di Puma and Zecca). In his summary of the jurisprudence, the Advocate General took a soberingly critical view of the ECtHR’s judgment in A and B v Norway and invited the ECJ not to follow its conclusions, proposing that the court instead resolve the various policy considerations at issue via the application of Article 52(1) of the Charter.[17][18] Given the divergent set of facts in each of the cases but similar legal considerations, the court’s analysis in Garlsson is set out in full below and a summary of the outcomes in the other cases is provided after that.

The ECJ’s analysis in Garlsson Real Estate

This case concerned a Consob – the Italian securities market regulator – investigation into securities market manipulation. At the end of its investigation, the Consob determined that Mr Stefano Ricucci and two companies under his direction, Magiste International and Garlsson Real Estate, had engaged in market manipulation with the objective of drawing attention to the securities of RCS MediaGroup SpA with a view to personal gain. On 9 September 2007, at the end of the administrative proceedings, the Consob fined the three parties jointly and severally EUR 10.2 million for market manipulation. On 2 January 2009, the fine was reduced to EUR 5 million by the Italian Court of Appeal, which also granted leave to appeal to the Italian Court of Cassation on a point of law.

Meanwhile, on 10 December 2008, in separate criminal proceedings, the Rome District Court convicted Mr Ricucci of market manipulation for the same conduct and sentenced him to a term of imprisonment of four years and six months. This sentence was subsequently reduced to a term of three years and then extinguished as a result of a pardon. The criminal sentence became final.

During his on-going appeal of the administrative fine before the Court of Cassation, Mr Ricucci argued that he had already been finally convicted of and sentenced with respect to the same acts in criminal proceedings in 2008. In light of this argument, the Italian Court of Cassation decided to refer the following two questions to the ECJ for a preliminary ruling:

- Does Article 50 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, interpreted in the light of Article 4 of Protocol No 7 to the ECHR, the relevant case-law of the European Court of Human Rights and national legislation, preclude the possibility of conducting administrative proceedings in respect of an act (unlawful conduct consisting in market manipulation) for which the same person has been convicted by a decision that has the force of res judicata?

- May the national court directly apply EU principles in connection with the ne bis in idem principle, on the basis of Article 50 of the Charter, interpreted in the light of Article 4 of Protocol No 7 to the ECHR, the relevant case-law of the European Court of Human Rights and national legislation?

The essence of the first question is, broadly put, given that Mr Ricucci has already been convicted of an offence in criminal proceedings, would subjecting him to and convicting him in administrative proceedings for the same offence constitute a violation of the ne bis in idem principle?[19]

As for the second question, the ECJ is being asked to determine whether the Charter is directly applicable. By way of further explanation, EU law distinguishes between legislative instruments that are directly applicable and legislative instruments that require further acts of implementation by the EU Member States. The significance of the distinction is that legislation having direct applicability creates a right of direct effect on individuals, i.e. that an individual can use EU legislation to enforce the rights provided under it against a Member State (vertical direct effect) or against another individual (horizontal direct effect). By contrast, if the legislation is not directly applicable (e.g. EU directives require implementation by the EU Member States), it does not create direct effect and, unless transposed into national law, an individual would not be able to enforce the right granted by that legislative instrument against a Member State. Rather, in this instance, the individual in question may be able to bring an action against the Member State in question for non-implementation.

The question of duplication of criminal proceedings for the same act

Court’s analysis under Article 50 of the Charter

The focus of the court’s analysis was on whether the two sets of proceedings and sanctions are criminal in their nature and whether they related to the same underlying conduct (idem).

First, given that the term of imprisonment handed down by the Rome District Court to Mr Ricucci clearly constituted a criminal sanction, it was a matter for the court to establish whether the parallel administrative proceedings and the fine imposed on Mr Ricucci were also criminal in their nature. In its assessment, the ECJ applied the Engel[20] criteria:

- the legal classification of the offence under national law;

- the intrinsic nature of the offence; and

- the degree of severity of the penalty liable to be incurred.

The proceedings at issue were classified as administrative and not criminal under national law, however, under the Engel test this alone is not determinative and regard must be had for the other two criteria. Accordingly, the ECJ established that, given that the Italian legislation provides for a significant administrative fine of between EUR 20,000-5,000,000 (with a potential to increase) for the offence in question, the punishment goes beyond what is purely restitutionary and has a punitive purpose to it, suggesting a criminal nature. The court also found that the penalty had a high degree of severity because of the potentially high ceiling to the fine, and concluded that the offence is therefore likely to be of a criminal nature.

Second, the ECJ considered that, given that the administrative fine of a criminal nature and the criminal conviction imposed on Mr Ricucci related to the same underlying conduct, i.e. market manipulation with a view to drawing attention to the securities of RCS MediaGroup, this would suggest the conduct in question relates to a set of concrete circumstances which are inextricably linked together and resulted in the conviction of Mr Ricucci. Accordingly, the idem limb of the test was also satisfied.

For the reasons set out above, the court concluded that it appeared that the national legislation at issue permitted the possibility of duplicating proceedings against a person who has already been finally convicted, thereby constituting a limitation of the ne bis in idem principle.

Court’s analysis under Article 52(1) of the Charter

Having reached the conclusion that the Italian legislation appeared to constitute a limitation on the ne bis in idem principle, the ECJ then considered whether the limitation may nevertheless be justified by the criteria under Article 52(1) of the Charter. Article 52(1) stipulates that, for a limitation to be justified, it must:

- be provided for by the law;

- respect the essence of the rights and freedoms subject to the limitation; and

- subject to the principle of proportionality, be necessary and genuinely meet other objectives of general interest recognised by the EU or the need to protect the rights and freedoms of others.

It was not in dispute that the legislation constituting the limitation appeared to satisfy first two criteria. Furthermore, the ECJ determined that it also appeared to meet an objective of general interest in seeking to protect the integrity of the financial markets of the European Union and public confidence in financial instruments so far as the duplicated criminal proceedings pursue complementary aims relating to different aspects of the same unlawful conduct at issue. However, in order to comply with the principle of proportionality, it is necessary that the duplicated proceedings and penalties do not exceed what is appropriate and necessary to attain the objectives legitimately pursued by that legislation. For these purposes, where there is a choice between several appropriate measures, recourse must be had to the least onerous and the disadvantages caused must not be disproportionate to the aims pursued. With respect to this, the court noted that the proportionality of the legislation in question cannot be called into question by simply by the fact that the EU Member State chose to provide for the possibility of duplication of penalties, because Article 14 of the Market Manipulation Directive itself provides for the possibility of such duplication and a finding to the contrary would deprive the EU Member State of that freedom of choice. Furthermore, the ECJ also held that, with regard to its strict necessity, the legislation at issue clearly and precisely sets out the circumstances in which market manipulation can be subject to a duplication of criminal proceedings.

Finally, the ECJ stated that the legislation at issue must also ensure that the disadvantages for the persons concerned resulting from the duplication are limited to what is strictly necessary in order to achieve the objective of general interest. In this context, the court considered two relevant criteria for assessment. First, the ECJ noted that this requirement implies the existence of rules ensuring coordination so as to reduce to what is strictly necessary the additional disadvantage associated with the duplication for the persons concerned. In this regard, the ECJ determined that the obligation for cooperation between the Consob and the judiciary required under national law is liable to reduce the resulting disadvantage of the duplication of proceedings for the person concerned. Second, the ECJ noted that the national laws must guarantee that that the severity of the sum of all the penalties imposed corresponds to the seriousness of the offence concerned and does not exceed the seriousness of the offence identified. With respect to this requirement, the ECJ noted that, in the event of a criminal conviction following criminal proceedings, the bringing of administrative proceedings of a criminal nature exceeds what is strictly necessary in order to achieve an objective of general interest in so far as the criminal conviction is such as to punish the offence committed in an effective, proportionate and dissuasive manner.

In reaching its conclusion, the court looked at a number of factors. First, the ECJ noted that market manipulation liable to be subject to a criminal conviction must be of a certain seriousness and that the penalties include a prison sentence as well as a criminal fine in a range which corresponds to that provided for in respect of the administrative fine.[21] According to the ECJ, it seemed that the act of bringing proceedings for an administrative fine exceeds what is strictly necessary in order to achieve the objective of general interest in so far as the criminal conviction is such as to punish the offence in question in an effective, proportionate and dissuasive manner. Second, the ECJ noted that the Italian legislation also provided that, if a fine has been imposed in administrative proceedings, any fine imposed in criminal proceedings must be limited to the part in excess of the penalty or sanction imposed by the administrative fine. The ECJ noted that, given that the legislation did not provide for the reverse situation in which any administrative fine imposed is limited to the part in excess of the criminal penalty, the legislation does not guarantee that the severity of all penalties imposed are limited to what is strictly necessary in relation to the seriousness of the offence concerned.

Accordingly, the court held that Article 50 of the Charter does not permit the possibility of bringing administrative proceedings of a criminal nature against a person in respect of unlawful conduct for which the same person has already been finally convicted in so far as this conviction is sufficient to punish that offence in an effective, proportionate and dissuasive manner.

The question of direct applicability with respect to individuals

As regards the second question, the ECJ reiterated that it is an established principle under pre-existing case law that provisions of primary law which impose precise and unconditional obligations not requiring any further action on part of EU Member States for their application create direct rights in respect of the individuals concerned. Therefore, the provisions of Article 50 of the Charter are directly applicable to individuals.

The ECJ’s analysis of the cases of Menci and Enzo di Puma and Zecca

Menci

The case of Mr Luca Menci concerned the non-payment of VAT. The Italian tax authority concluded that Mr Menci, a sole trader, had not paid VAT to the sum of EUR 282,496. The authority ordered Mr Menci to pay the VAT due and also imposed on him an administrative fine representing 30% of the amount of unpaid VAT. This decision became final. After the conclusion of the administrative proceedings, criminal proceedings for non-payment of VAT were initiated against Mr Menci in the Bergamo District Court. As in the case of Garlsson, the ECJ concluded that the parallel proceedings at issue constituted a limitation on the principle on ne bis in idem. However, unlike in Garlsson, the ECJ concluded that these proceedings appeared to be justified because the criteria under Article 52(1) of the Charter seemed to have been satisfied.

In Menci, the ECJ concluded that the national legislation restricted the bringing of criminal proceedings to offences which are particularly serious, namely offences relating to an amount of unpaid VAT which exceeds EUR 50,000 and for which the national legislation has provided for a term of imprisonment justifying the need to initiate criminal proceedings in addition to the administrative proceedings. Importantly, unlike in Garlsson, the court held that the severity of penalties imposed did not exceed the seriousness of the offence identified because the relevant Italian law contains a provision which definitively prevents the enforcement of administrative penalties after a subsequent criminal conviction, and the voluntary payment of any administrative penalty constitutes a special mitigating factor to be taken into account in the context of the criminal penalty. It is for this reason that the court concluded that the duplication of proceedings under the Italian legislation does not exceed what is strictly necessary in order to ensure the objective of general interest of VAT collection.

Joint cases of Enzo Di Puma and Zecca

The joint cases of Di Puma and Zecca concerned several instances of insider trading. In at least one instance, Mr Zecca, an employee at a major accountancy firm, shared with Mr Di Puma insider information relating to the takeover of a company as a result of which Mr Di Puma acquired shares in the target. On 7 November 2012, the Consob imposed administrative fines on both individuals with respect to this conduct. In due course, the two appeals ended up before the Court of Cassation. It was argued that Mr Di Puma had already been subjected to, and acquitted in, criminal proceedings for a lack of evidence with respect to the same underlying conduct as that covered by the administrative decision in question.[22]

With regard to the ne bis in idem principle, the ECJ went through the same analysis as in Garlsson and concluded similarly that the proportionality test had not been met. In this case, the court held that the bringing of proceedings for an administrative fine of a criminal nature “clearly exceeds” what is necessary in order to achieve the objective of general interest of protecting the integrity of the financial markets where a final criminal judgment of acquittal had already concluded that the acts capable of constituting insider trading had not been established. The court also noted that this finding does not preclude the reopening of criminal proceedings where there is evidence of new or newly discovered facts or if there has been a fundamental defect in the previous proceedings which could affect the outcome of the criminal judgment, as provided for under the ECHR.[23]

Key takeaways from and observations on the ECJ’s analysis

Summary of the ECJ’s approach and potential shortcomings

The first takeaway is that, although each of the cases were very much decided on their relevant facts and the specific framework of the applicable national legislation, the crux of the ECJ’s underlying analysis is that: (i) administrative penalties, at least in the context of financial services (and unless they are purely restitutionary), are likely to be of a criminal nature; (ii) a bifurcated national system providing for parallel administrative and criminal penalties constitutes a limitation on the principle of ne bis in idem; and (iii) such a limitation will only be justified if the EU Member State in question provides a clear legal framework for it, including setting out how the administrative and criminal proceedings can be conducted in parallel with minimal additional disadvantage for the defendant and how any parallel penalties are to be limited by reference to each other so that they do not exceed the seriousness of the offence committed.

It can also be observed that the ECJ generally considers criminal proceedings and sanctions to be more severe than administrative proceedings and sanctions (of a criminal nature).[24] Furthermore, the court also requires that, where there is a choice of several appropriate measures, recourse must be had to the least onerous and the disadvantages caused must not be disproportionate to the aims pursued.[25] This finding suggests a higher burden would need to be satisfied to justify the bringing of administrative proceedings after criminal proceedings have already been conducted than it would be the other way around. However, this does not take into account the fact that, broadly speaking, as a matter of practice and law, where national systems provide for both administrative and criminal offences in relation to the same underlying conduct, criminal proceedings typically require not only the satisfaction of a higher criminal burden of proof but also additional elements to the offence, e.g. a subjective element such as relevant intent. The significance of this could be observed in the facts and outcomes of the Enzo Di Puma and Zecca cases.

In brief, the Consob started an investigation into both individuals in 2009 and this investigation concluded in 2012 with the imposition of fines and bans from holding positions in publicly listed companies. In 2013, the Milan Court of Appeal dismissed Mr Di Puma’s appeal, but upheld Mr Zecca’s appeal on procedural grounds. Meanwhile, in 2011, the Consob also shared with the Milan Prosecutor’s Office a report containing the results of its investigation into the conduct in question. The prosecutor brought a case against Mr Di Puma and Mr Zecca in the Milan District Court, which in 2014 resulted in their acquittal for lack of evidence. This judgment became final because the prosecutor decided not to appeal it.

In reaching the conclusion that the parallel proceedings appeared to violate the ne bis in idem principle for the reasons set out above, the ECJ made two remarks. First, that, under the relevant Italian legislation, the Consob was free to participate in the criminal proceedings and was moreover required to send to the judicial authorities the documents collected during its investigation. Second, that the criminal proceedings could be reopened, where appropriate, where there is new evidence of new or newly discovered facts.

The author has not looked at the actual details of the criminal trial of Mr Di Puma and Mr Zecca. However, regardless of the actual facts, applying the ECJ’s reasoning, it would not seem entirely implausible that the criminal trial may well have resulted in the acquittal of the defendants because the prosecution may have failed to satisfy a higher burden of proof required to prove the criminal offence (by contrast to the burden of proof required to be satisfied for the administrative offence) or that the prosecution may have failed to establish an additional element to the criminal offence (e.g. intent) that is not required to be satisfied for the administrative offence. Having failed to establish this higher threshold and the matter becoming res judicata by virtue of not having been appealed by the prosecution meant that the Consob was precluded from imposing the administrative fine, even though: (i) the administrative proceedings had been started first in time; (ii) the administrative decision had been imposed (but did not become final) before the criminal decision; and (iii) the administrative offence may well entail a substantially lower evidentiary threshold.

There are therefore a number of (possibly unintended) consequences to this outcome. First, it may open the possibility for creative defence counsel to successfully game the system so as to prevent administrative proceedings being brought against a client who has violated the law and ought rightly to be punished via securing an acquittal in criminal proceedings. Second, it may lead to a situation in which public authorities may be incentivised to (subject to any statute of limitation constraints) delay the conduct of any criminal proceedings until the administrative decision has become final before starting the conduct of criminal proceedings. Given that it can in different jurisdictions take several years to exhaust all avenues of appeal, this may well lead to a situation in which an individual is subjected to over a decade of duplicative litigation in relation to a single offence. Perhaps somewhat ironically, this outcome would instead call in favour of the introduction of a temporal element to the proceedings, such as the one set out in A and B v Norway. Therefore, it is hoped that national governments will instead respond by adapting national frameworks so as to avoid bifurcated proceedings altogether, or by ensuring that any bifurcated proceedings are carried out within a clear, predictable and transparent framework in which the relevant authorities cooperate closely with each other.

Implicit rejection of A and B v Norway by the ECJ?

The second and, subject to the paragraph above, very welcome takeaway from these judgments is that the ECJ appears to have implicitly rejected the application of the “sufficiently close connection in substance and time” test as applied by the ECtHR in A and B v Norway. The ECJ does not expound on AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona’s highly critical analysis of the reasoning adopted in that case, but it does not give it any substantive judicial treatment either – the only mention of A and B v Norway is in the Menci judgment[26] in which the ECJ concludes that the level of protection afforded to the ne bis in idem principle in Menci does not conflict with the level guaranteed by the ECtHR.

The most likely interpretation is that the ECJ does not approve of the ECtHR’s approach in A and B v Norway – whether the reason being the difficulty in applying the test and the ensuing jurisprudential uncertainty, or the step backwards in the protection afforded to individuals – but does not reject it outright for reasons of institutional respect between the two courts. In some ways, the ECJ’s approach arguably demonstrates the fundamental shortcoming of the “sufficiently close connection” test – given the uncertainty inherent in its application, it is as easy to disapply as it is to apply. Alternatively, it could be argued that the ECJ may not necessarily be opposed to the ECtHR’s approach in A and B v Norway, but has simply decided to adopt a higher standard of protection for individuals under EU law as per Article 52(3) of the Charter. In any event, individuals attempting to enforce their rights under the ECHR will at least for the time being have to bear the brunt of being uncertain as to where they stand under that strand of case law.

Brexit considerations

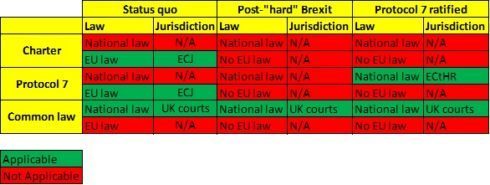

The third takeaway is that, post Brexit, UK residents will lose the benefit of the protections afforded by the ne bis in idem principle under both the Charter and the Protocol. This is explained below by reference to three different scenarios – the status quo, the “hard” Brexit scenario and the scenario in which the UK ratifies Protocol 7 post-“hard” Brexit. A table illustrating each of these scenarios is included at the end of this section.

The status quo

The existing legal situation in the UK with respect to the ne bis in idem principle can be described as follows. First, Article 50 of the Charter applies to the interpretation of EU law in the UK. Second, the UK has neither signed nor ratified Protocol 7. However, Article 4 of Protocol 7 nevertheless also applies to the interpretation of EU law in the UK by the ECJ (but not by the ECtHR) [27] because Article 52(3) of the Charter requires that the rights granted by both the Charter and the ECHR be interpreted consistently.[28] Third, Protocol 7 does not apply to the interpretation of UK national law, because it has not been ratified by the UK. Fourth, independently of international laws, English law also recognises the principle of double jeopardy (the common law equivalent of ne bis in idem) via the common law principle of autrefois acquit and various provisions of the Criminal Justice Act 2003.

“Hard” Brexit scenario

The post-“hard” Brexit legal situation in the UK with respect to the ne bis in idem principle can be described as follows. First, as the EU’s treaties will cease to have effect in the territory of the UK, article 6 of the amended Treaty on European Union which incorporates the Charter will cease to have effect in the UK, so Article 50 of the Charter will no longer apply. Moreover, given that Article 50 of the Charter is concerned with the interpretation of EU law, there would in any case be no more EU law to interpret in the UK. Second, the ECtHR’s case law on the interpretation of the ne bis in idem principle would no longer apply, because Article 52(3) of the Charter would no longer apply, the ECJ’s jurisdiction would no longer apply and, in any case, there would be no more EU law in the UK to interpret. Third, the common law principles of autrefois acquit and various provisions of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 would still continue to apply – in effect the legal framework would be the same it was before the incorporation of the Charter into EU law after the signing of the Lisbon Treaty.

In practice, Brexit is likely to have considerable implications on the application of the ne bis in idem principle in the UK. As the wealth and significance of the ECJ and ECtHR case law demonstrates, the ne bis in idem principle has over the years granted relief to applicants who would not have necessarily been able to secure such relief under national law provisions or national courts, and put increased pressure on national governments to ensure that bifurcated proceedings are conducted in a manner that is fair to the defendants. Furthermore, it should be noted that, even though the Charter and (in the UK) Protocol 7 only apply to instruments of EU law and not national law, in practice, the attempts of EU law at harmonising the EU’s regulatory frameworks, in particular with respect to regulated professions and industries such as financial services, means that many seemingly national laws and procedures in fact have an EU dimension to them and therefore provide for a means for individuals to invoke the protections under Article 50 of the Charter and Article 4 of Protocol 7. The broad and pervasive nature of EU law was illustrated in the case of Åkerberg Fransson – before which few considered that the collection of VAT had an EU law dimension to it.[29] This is further illustrated by the cases discussed in this article, which covered market manipulation, insider trading and VAT collection. Accordingly, a “hard” Brexit would deprive many in the UK of the chance to take their case to be heard by the ECJ or the ECtHR.

UK ratifies Protocol 7

It is also possibility that the UK government may choose to sign and ratify Protocol 7 and submit to the jurisdiction of the ECtHR as regards the ne bis in idem principle (this can be done in the event of a “hard” Brexit as well as in combination with any Brexit deal). Under this approach, Protocol 7 would apply to provisions of national law (whereas under the status quo it only applies to EU law) and its interpretation would be under the jurisdiction of the ECtHR (whereas under the status quo it is under the jurisdiction of the ECJ). However, this approach would seem unlikely at least in the current Brexit-charged political climate, where national sovereignty is paramount and there is still talk of replacing the Human Rights Act with a “British Bill of Rights”.[30] Finally, should the UK government nevertheless choose to ratify Protocol 7, it should be borne in mind that A and B v Norway is the latest precedent under the ECtHR case law and it may very well be the case that the ECtHR will not change its course and will not adopt, or have the means to adopt, the broader protections under the ne bis in idem principle provided for by the ECJ.

Conclusion

The ECJ’s judgments in the four cases at issue attempt to strike a fair balance between the protection of individuals via the ne bis in idem principle while at the same time introducing a more clear analytical framework that EU Member States (and potentially other Council of Europe states in due course) can use to determine whether their legal systems are compatible with Article 50 of the Charter and Article 4 of Protocol 7. However, the ECJ’s approach is not without its shortcomings within the existing framework of fragmented national systems and national governments would do well to review bifurcated systems in particular to ensure that, on the one hand, defendants are tried and punished in a fair and transparent manner and, on the other hand, wrongdoers are not able to circumvent justice.

It is also a welcome observation that the ECJ appears to have implicitly rejected the ECtHR’s approach in A and B v Norway and opted instead for a test that is easier to apply by the courts and affords more protection to individuals. Finally, any Brexit outcome is likely to lead to a lesser standard of protection being afforded to individuals due to the loss of Article 50 of the Charter, however, this outcome can at least in part be mitigated by the UK ratifying Protocol 7.

[1] Article 267 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union – the reference for a preliminary ruling procedure is a recourse available to the courts of EU Member States to refer for the ECJ’s analysis a question of interpretation or validity of EU law. The ECJ addresses points of law only and its judgments are binding on the courts of all EU Member States. Therefore, it is important to note that the ECJ does not apply its conclusions to the cases at hand, but rather it is a matter for the national court to apply the ECJ’s interpretation to the facts of each case.

[2] Article 4 – Right not to be tried or punished twice.

- No one shall be liable to be tried or punished again in criminal proceedings under the jurisdiction of the same State for an offence for which he has already been finally acquitted or convicted in accordance with the law and penal procedure of that State.

- The provisions of the preceding paragraph shall not prevent the reopening of the case in accordance with the law and penal procedure of the State concerned, if there is evidence of new or newly discovered facts, or if there has been a fundamental defect in the previous proceedings, which could affect the outcome of the case.

[3] Article 50 – Right not to be tried or punished twice in criminal proceedings for the same criminal offence.

No one shall be liable to be tried or punished again in criminal proceedings for an offence for which he or she has already been finally acquitted or convicted within the Union in accordance with the law.

[4] Article 52 – Scope of guaranteed rights.

- In so far as this Charter contains rights which correspond to rights guaranteed by the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, the meaning and scope of those rights shall be the same as those laid down by the said Convention. This provision shall not prevent Union law providing more extensive protection.

[5] Sergey Zolotukhin v Russia, no. 14939/03.

[6] Case C-617/10 Åkerberg Fransson.

[7] The so-called Engel criteria are set out in more detail below but, for present purposes, it deserves to be noted that administrative proceedings can also be criminal in their nature despite not being classified as such under national law.

[8] A and B v Norway, nos. 24130/11 and 29758/11.

[9] A more comprehensive criticism of the ECtHR’s judgment can be found, for example, in the opinion of Advocate General Campos Sánchez-Bordona in the case C‑524/15 Luca Menci, paragraphs 55-94.

[10] Jóhannesson and Others v Iceland, no. 22007/11.

[11] The EU’s judges are assisted by eleven Advocates General. It is typical for an Advocate General to issue a legal opinion in cases involving new points of law. However, the court is not bound by opinions and can reach its own conclusions independently.

[12] Opinion of AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona in the case C‑524/15 Luca Menci, paragraph 56.

[13] In summing up conclusions from existing case law, the ECtHR noted that Protocol 7 had only been signed in 1988, had not been ratified in all states (including the UK; more on this in the conclusion), and that some states had expressed reservations or declarations regarding the interpretation of “criminal” in those states. The court further noted that the imposition of penalties under both administrative and criminal law was a widespread practice in the various states and the manner in which these were implemented varied greatly from one state to another. Finally, the court noted that six states had intervened in the proceedings to express views and concerns on questions of interpretation of the ne bis in idem principle post Åkerberg Fransson.

[14] Case C-524/15 Luca Menci.

[15] Case C-537/16 Garlsson Real Estate.

[16] Joined Cases C-596/16 Enzo Di Puma and C-597/16 Antonio Zecca.

[17] Article 52 – Scope of guaranteed rights

- Any limitation on the exercise of the rights and freedoms recognised by this Charter must be provided for by law and respect the essence of those rights and freedoms. Subject to the principle of proportionality, limitations may be made only if they are necessary and genuinely meet objectives of general interest recognised by the Union or the need to protect the rights and freedoms of others.

[18] Since the ECJ’s decision in Åkerberg Fransson, the ECJ had held in Case C-129/14 PPU (Spasic) that any limitations on the principle of ne bis in idem under Article 50 of the Charter may be justified if the conditions under Article 52(1) are satisfied. This approach could be used to reign in the arguably overly broad interpretation of the case law under Åkerberg Fransson and provide more judicial controls to limit its application. There is no direct equivalent to Article 52(1) of the Charter under the ECHR.

[19] The question is more nuanced. First, what is really at issue in the question is not so much the conduct of proceedings or the decision to issue fines, but whether the relevant provisions of national law providing for the possibility of duplicated proceedings and duplicated fines are incompatible with the Charter. The Directive in question allows for, and Italian legislation specifically provides for a bifurcated system under which an individual can be subjected to both criminal and administrative proceedings and fines for the offence of market manipulation. Second, there is a jurisdictional question. The ECHR is an international treaty and its provisions apply to national legislation directly. By contrast, by virtue of being an instrument of EU law, the provisions of the Charter only apply with respect to EU law. In this case there was no issue of jurisdiction because the provisions of national law in question had been derived from Italy’s transposition into national law of the EU’s Market Abuse Directive (Directive 2003/6/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2003 on insider dealing and market manipulation (market abuse)).

[20] Engel and Others v The Netherlands, nos. 5100/71; 5101/71; 5102/71; 5354/72; 5370/72.

[21] Under the relevant legislation, the financial penalties for the criminal offence were set statutorily at between EUR 20,000 and EUR 5,000,000, but a court may increase the fine by up to three times the amount or up to an amount ten times greater than the proceeds or profit obtain from the offence. The financial penalties for the administrative offence were set statutorily at between EUR 100,000 and EUR 25,000,000 with an option to be increased by the court.

[22] The legal situation at issue was in fact a little more complicated, although for these purposes the analysis broadly followed the same lines. Briefly, Article 14(1) of the Market Abuse Directive requires that, without prejudice to the right to impose criminal sanctions, Member States must ensure that appropriate administrative measures can be taken and administrative sanctions can be imposed on individuals for market abuses. This provision had been implemented into national law. Separately, an instrument of Italian legislation (not having EU law as its origin) stipulates that, in certain circumstances, a final judgment in criminal proceedings has the force of res judicata in civil or administrative proceedings relating to a legitimate right or interest recognition of which depends on establishing the same material facts as those which were the subject of the criminal proceedings. In other words, it was argued that national legislation by which criminal proceedings confer the force of res judicata on matters required to be adjudicated administratively under EU law were in conflict with that provision of EU law in so far as the national legislation prohibited such adjudication. Having addressed this question (there was no conflict), the ECJ then also analysed the facts in the case in light of Article 50 of the Charter.

[23] See Article 4(2) in footnote 2 above.

[24] See, for example, case C-524/15 Luca Menci, paragraph 45.

[25] Ibid, paragraph 46.

[26] Ibid, paragraphs 60-62.

[27] In Blokker v The Netherlands, no. 45282/99, the ECtHR confirmed that there is no right to apply to the ECtHR with respect to the ne bis in idem principle if it has not been ratified by the state in question.

[28] In Åkerberg Fransson, the ECJ held that, in interpreting the provisions of the Charter in so far as they align with the same provisions in the ECHR, the level of ratification of the ECHR provisions by the individual EU Member States has no bearing on its use as a criterion for the interpretation of Article 50 of the Charter.

[29] Case C-617/10 Åkerberg Fransson, paragraphs 25-27.

[30] Broadly speaking, the purpose behind the Human Rights Act 1998 was to incorporate into national legislation various provisions of the ECHR so as to provide recourse through national courts without having to apply to the ECtHR. The Human Rights Act 1998 does not incorporate Protocol 7.

Contact Us